Can These Two Exercises Prevent Menopause Bone Loss as Effectively as Hormone Therapy?

The study I keep coming back to, and another one that explains it

I’ve seen this story many times now and its eerily family. Let’s revisit it with someone we’ll call Jane.

Jane’s been exercising and eating right most of her life. When she finally gets a DEXA scan a few years post menopause, she finds she has osteoporosis in her spine and osteopenia at her hip.

She works to increase bone density by jumping and doing strength training, but a follow up DEXA shows worsening results.

But she wonders if she knew sooner that maybe she could’ve done more to help her bones. She’s offered the choice between hormone therapy or medication.

Stories like this always lead me back to a study done almost 20 years ago. Its results are not only intriguing, but if replicated—and refined—could help many women in the same boat.

First, let’s discuss the effects of menopause on bone density.

The rapid bone loss phase

While women’s bone density peaks around age 30, significant bone loss accelerates in the year leading up to and the two years following menopause due to declining estrogen levels.

During this three-year period, bone loss averages 2.46% per year. This drops to 1.06% more than two years after the final period.

According to results from The Study of Women’s Health Across a Nation (SWAN), cumulative bone loss stretching 5 years before the FMP and 5 years after is about 10% but varies based on ethnicity, genetics and lifestyle.

For example, Caucasians lose an average of 10.6% in the lumbar spine and 9.1% in the femoral neck. African Americans fare better with 9.6% and 8%. And the Japanese and Chinese lose at rates of 10.1% and 10.8% and 12.6% and 10.3%, respectively.

In short, right before and following menopause, bone loss speeds up.

DEXA at 65??

Bone mineral density (BMD) testing is the “gold standard” for diagnosing osteoporosis because of the established relationship between BMD and fracture risk.

BMD is determined using a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan, which takes about 5-10 minutes. It checks how dense bones are by using two low dose X-ray beams.

DEXA measures bone density in different areas, typically the spine and hip, to give an average BMD. This is compared to a healthy 30-year-old’s bones, which is T score of 0.

A normal score ranges from one standard deviation lower than that (-1) to anything higher. Osteopenia, the low-bone mass stage before osteoporosis, is a T score between -1 and -2.5. Osteoporosis is A T score below -2.5.

There are also Z scores that compare your bone density to others your same age, but T scores are used to determine bone mass. It’s important to note that each standard deviation on T and Z scores account for about 10-12% bone mass.

You can see the importance of bone health prior to menopause, especially given that as many as 25% of women 35-50 already have low bone mass (osteopenia).

This jumps to more than half of US caucasian postmenopausal women have osteopenia and 30 percent have osteoporosis.

Yet the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening at 65! It’s just madness, I tell you. Now onto the study.

Comparing high-intensity resistance weight training to HRT

Researchers wanted to compare how 1-year resistance training using two exercises twice a week (back squat and deadlift) affected bone mass compared to HRT in early menopausal women.

Researchers separated 141 women into four groups for the study.

1) Non-HRT plus RT (Squat and deadlift twice a week)

2) HRT plus RT

3) HRT no RT

4) Control (no HRT or RT)

After a year, the control group lost an average of 3.6% bone mass in the spine. HRT with no RT showed bone loss of -.0.66%. RT without HRT revealed gain in BMD of .43% while HRT plus RT showed 0.70% gain.

For these women, in their rapid bone loss phase, RT prevented bone loss as much as HRT alone. While there was more of an increase with HRT plus RT, it was not statically significant.

I find this amazing because it included just two exercises twice a week. The deadlift and back squat both use compound movements, using a barbell.

Although there are other studies that measure bone density and exercise in midlife and older women, there have been no others that compare it to hormone therapy.

Where are the follow-up studies?

(I feel like I’m always asking this)

The closest I could find was the work by Belinda Beck on the Liftmor trial with older postmenopausal women.

Load and bone metabolism

In the early 2010s, Australian Griffith University’s Belinda Beck, a professor in Health Sciences & Social Work, was puzzled by the failure of resistance training trials on women with osteoporosis to demonstrate bone growth. After all, studies with loading animals showed this is feasible.

We know that bones respond to heavy loads by becoming stronger; this process activates osteocytes, recruiting the building of new bone for support. This is known as Wolff’s Law.

Bones also react to a lighter load by releasing calcium, as is shown in astronauts who go into space and lose bone mass. This is also why lower weight women are at greater risk for osteoporosis.

Taking a closer look at the studies, she found that in order to protect osteoporotic women, most exercises were single-muscle focused and of moderate intensity, between 8-12 repetitions at 67-80% one rep max.

“There’s this worry that if you’ve got a very frail skeleton that you might hurt somebody. There’s also a very real belief that patients won’t do it,” Beck said in this interview at Medical Republic. “The problem is, when it comes to growing bone, size matters. That means that the magnitude of the strain that you’re loading the bone with matters, and we’ve known this for years.”

This led her to develop a new protocol called the LIFTMOR (Lifting Intervention For Training Muscle and Osteoporosis Rehab), which was actually similar to the 2007 study.

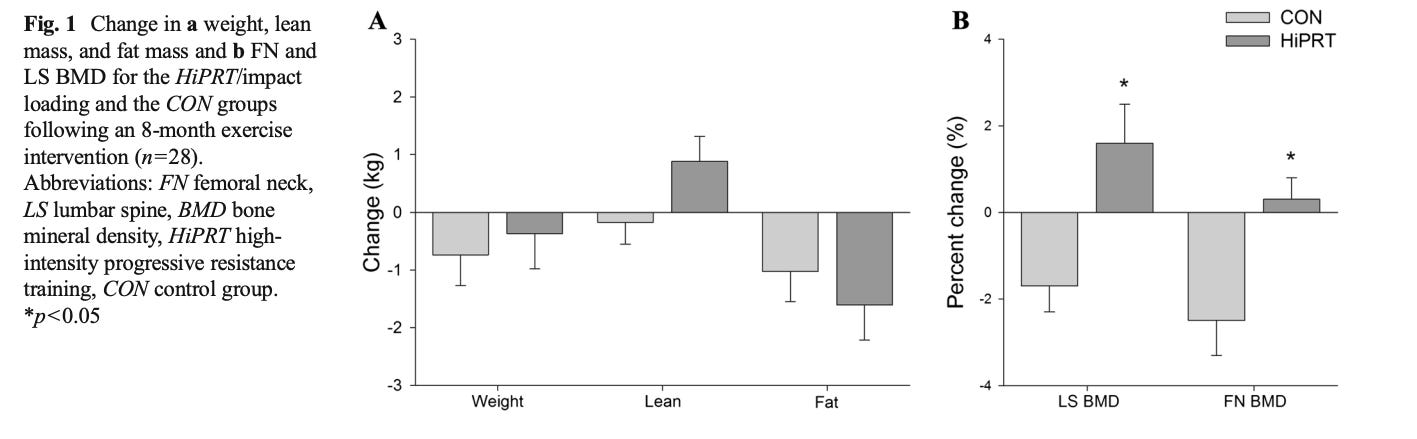

In this study, participants went to supervised lifting sessions twice a week, which included barbell back squats, deadlifts and overheard press. It also included jumping chin-ups with drop landings.

What makes these exercises so beneficial is they are large multi-joint exercises that involve multiple muscles and bone sites, such as the spine and hip.

All-in the supervised training was a 30-minute session, twice a week. The participants did 5 sets and 5 repetitions progressively adding on weight to 85% 1-rep max. The first trial with women (average 66) was 8 months long. This amount of time is important because it takes about that long to build new bone.

And the study showed that these women could indeed build new bone safely. Those in the intervention improved height, femoral neck and lumber spine bone density, and functional performance.

A follow up study with more women showed similar results. Not only that, but it reduced kyphosis, the curvature in the spine that is a hallmark of osteoporosis.

“We believe this overly conservative approach has contributed to an unnecessary stagnation in the field. The evidence from the LIFTMOR trial that high-intensity loading can indeed be tolerated by postmenopausal women with low to very low bone mass justifies a quantum change in attitude in this regard.”

-Beck et al, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 2018

Shouldn’t we start earlier?

When I learned about “lift heavier,” I started randomly choosing heavier dumbbells in my bootcamp class.

But I eventually moved over to barbells at a different gym, learning how to do these compound movements correctly with progressive overload.

It’s not. And I repeat, it’s not about reaching X amount of weight. It’s about whatever weight challenges you.

And I watched as my bone density (which lucky for me was normal) go up even more. But most importantly, was that I understood the right form to do the exercises effectively.

So, we have this 2007 study showing that adding these two exercises might be a way to lessen bone loss during the menopause transition. And we have the LIFTMOR study which shows you can add bone around age 65 with already low bone mass.

Although we need more research, doesn’t it make sense to test bone density in the early 40s and intervene before osteoporosis sets in? My guess is the women with osteoporosis at menopause likely had osteopenia in their 40s.

Supervision and proper training are key

Wherever you are in midlife, remember that getting supervision is important. If you are healthy and free of bone issues, a trainer can help initially.

But if you have osteoporosis or osteopenia, constant supervision is important. Beck launched the Onera program to provide women with supervised, high-intensity weight training at dedicated physical locations.

Most are in Australia, but some are popping up in the US and other areas. They do offer trainings so the possibility for more is there if there’s interest (maybe suggest it to your gym or trainer—I know I will).

And the data from this program is showing amazing results from the data they’re collecting showing that 86% see increased bone mass in the lumbar spine and 69% in the hip.

But back to the question posed in the post title: Can these two exercises prevent menopause bone loss as effectively as hormone therapy?"

We don’t have enough data to know for sure but it’s certainly a possibility.

What I like about this is the simplicity, 2-3 compound movements twice a week.

What do you think?

This information is for educational purposes and is not meant to replace medical advice. Before trying compound movements seek help from the appropriate health professional to prevent injury. To find out more about the Onera program go here.

This research is fascinating. And you're on point when you say that women need DXA tests and guidance in their 40's - not at 65 when they've already lost bone mass.

I just got a DEXA and my BMD has improved! I don't know if it is the HRT or that I have been lifting more seriously and progressively since my last DEXA 1.5 yrs ago. Just sharing that it can improve! I am going to continue lifting because actually although I have been on HRT about that same amount of time I wasn't really absorbing it so I am not sure how helpful it has been.