I’ve been wanting to write about fatigue for a while now. After all the research I’ve done, I feel like I understand it much better. I’ll read about midlife women who have tried everything and still feel fatigue and I believe it.

That’s because the mainstream thinking of fatigue misses underlying causes. One study found 1 out of 5 midlife women complain of fatigue, but my guess is it's more than that. Because there is a fatigue continuum and many of us women live with a certain amount, even when we don’t have to.

I also suffered from fatigue, but I didn't understand its impact until it got better. I luckily stumbled upon my solution, but I want to help other women take a more direct approach.

So, let’s talk about some of these root causes of fatigue we might be missing. But first, let’s define what fatigue is.

What is fatigue?

Researchers tried to answer this question and found that one agreed-upon definition of fatigue doesn’t exist. That’s because fatigue is multidimensional and there is no one way to assess, identify, and measure it.

Although healthy people also experience fatigue, it is more prevalent among those with acute and chronic medical conditions. Sometimes fatigue can be a pre-disease state, which makes digging into its cause important. Its extreme form is chronic fatigue syndrome, which is defined a fatigue for 6 months that includes at least four of the following:

· Increased feeling of tiredness after activity

· Sleep problems

· Muscle and join pain

· Head and neck pain

· orthostatic disturbances

· Cognitive issues

There are physical, cognitive, and mental dimensions of fatigue. Today, I’m going to stick with the physical. I like this definition from the Mayo Clinic:

Fatigue reduces energy, the ability to do things and the ability to focus. Ongoing fatigue affects quality of life and state of mind.

There are certain ingredients we need or order to have sufficient energy. First is oxygen. Not only do cells and tissues need oxygen, but there needs to be a way to transport it. Cells and tissues also need essential nutrients to be transported. And this is done with good circulation and blood flow.

So let’s go through a checklist of sorts to figure out where the breakdown could be.

First stop, Iron

I was in my late forties and low on energy. I wrongly assumed these were normal symptoms of perimenopause. Then I got diagnosed with iron deficiency anemia and everything changed.

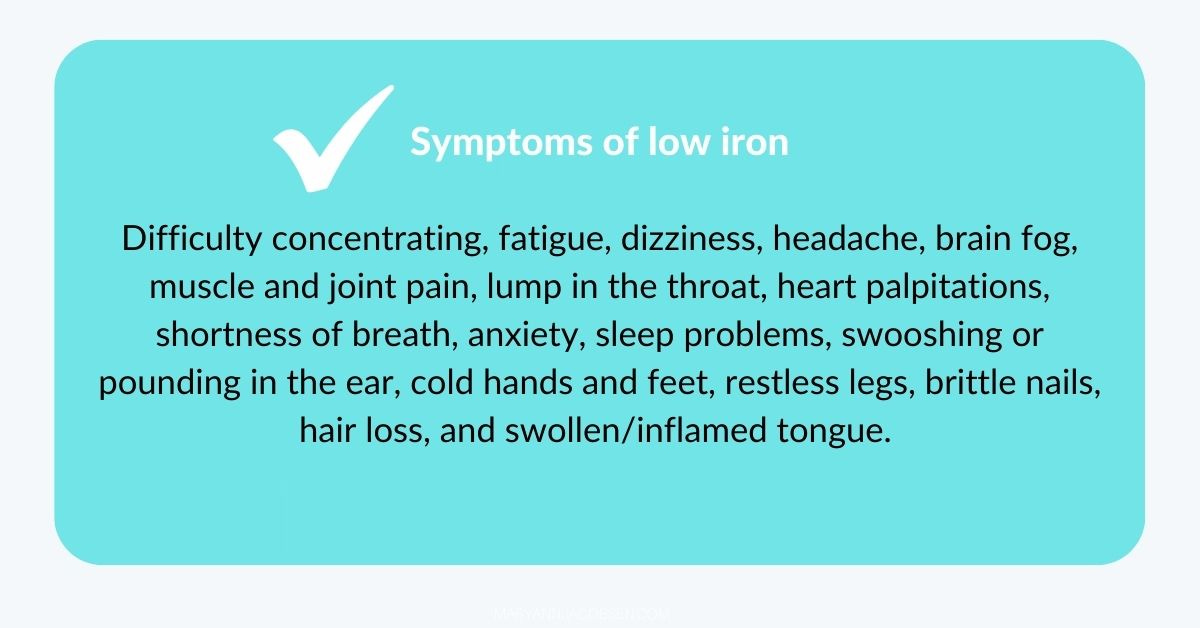

Right now, many still cycling midlife women have low iron levels. That is the primary cause of fatigue in this age group. That’s because iron is the heme part of hemoglobin, and its job is to carry oxygen to cells and tissues. But it’s also a cofactor for different functions in the body. When iron stores dip, the body simply doesn’t function as well as it should.

Ferritin is the most sensitive marker of iron deficiency, especially iron stores. Research shows that a ferritin <50mcg/L is linked to unexplained fatigue in women. Yet it’s missed because too many healthcare provider’s offices only check hemoglobin. And when they check ferritin, their cutoff is too low. Problem is when that’s depleted and anemia occurs, most women have had low iron stores for years.

Ferritin gradually rises after menopause and the risk of iron deficiency will decline. Yet another type of iron deficiency is possible, and this is called functional iron deficiency.

This is when you have adequate stores, so ferritin is normal or even elevated, but your body cannot access the iron. This typically happens when there is some type of inflammation going on. It can also occur when taking certain medications, like proton pump inhibitors for GERD.

The lab to look at post menopause is iron saturation, anything below 20% or above 40% should be investigated. As we get through menopause, a small percentage of women may find they have hemochromatosis, an inherited iron overload disorder. That’s because years of periods mask this issue and it’s only when periods stop that the buildup of iron occurs.

This is how I’m handling it. I’m in late perimenopause and when I get a period, it's light. My last ferritin was good (70mcg/L) but at my next physical I’m going to ask for a complete iron panel which will include iron saturation to just monitor it.

Knowing your body has enough iron stores and access means you can transport oxygen throughout the body. But that’s not all you need.

Don't forget folate and vitamin B12

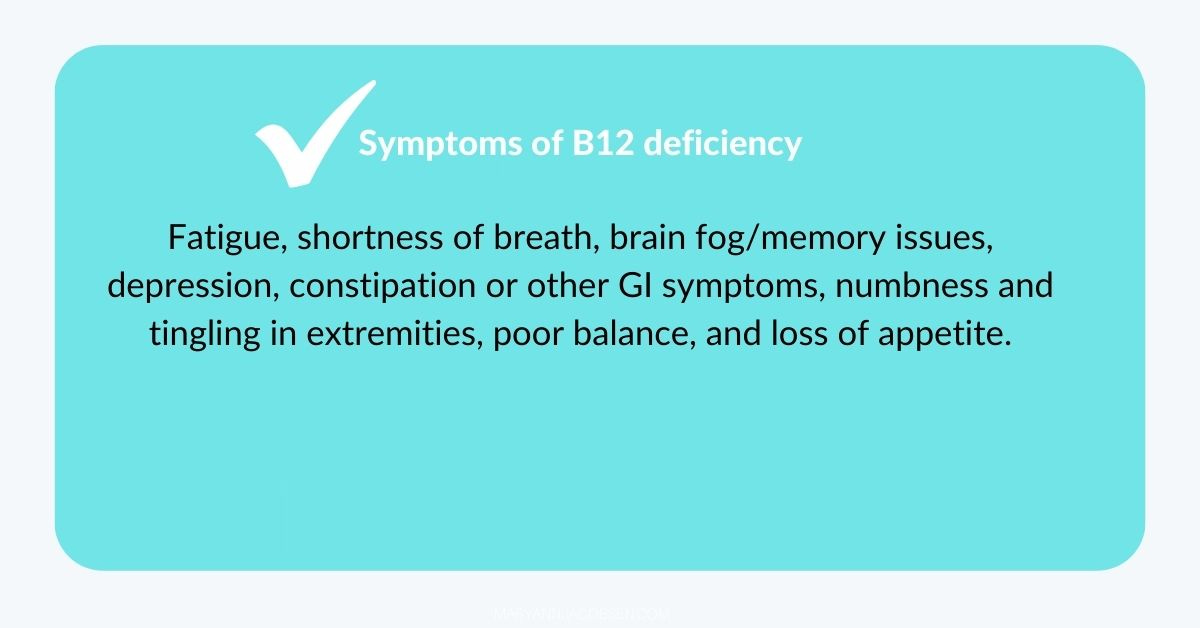

We need folate and vitamin B12 for the formation of red blood cells. When one or both are low, another type (macrocytic) of anemia can occur, also causing fatigue.

Declining B12 is usually due to changes with absorption with aging and decreases in stomach acid. A study revealed that 36% of post-menopausal women had a stomach pH level higher than the required 1-2 pH level to break down B12 from food. This is why supplemental B12 is recommended after 50.

Folate may decline with a low intake of grains, legumes, and citrus fruits. This can easily happen when following certain diets like keto, reducing carbs, and not taking a multivitamin.

If your iron status is optimal and you're still fatigued, ask your health care provider to check your folate and B12 levels. I provide more details in my FREE biomarker guide you get when signing up for this newsletter.

In short, having adequate iron, folate and B12 helps keep your red blood cells healthy to transport oxygen. But it still might not be enough.

The silent player: nitric oxide

The respiratory system is a two-gas system involving oxygen and carbon dioxide.

When we breathe in, blood passes through the lungs where oxygen attaches to hemoglobin. Red blood cells then transfer oxygen to the rest of the body’s cells and tissues. After supplying oxygen, empty red blood cells attach to waste products like carbon dioxide, which are excreted when we exhale.

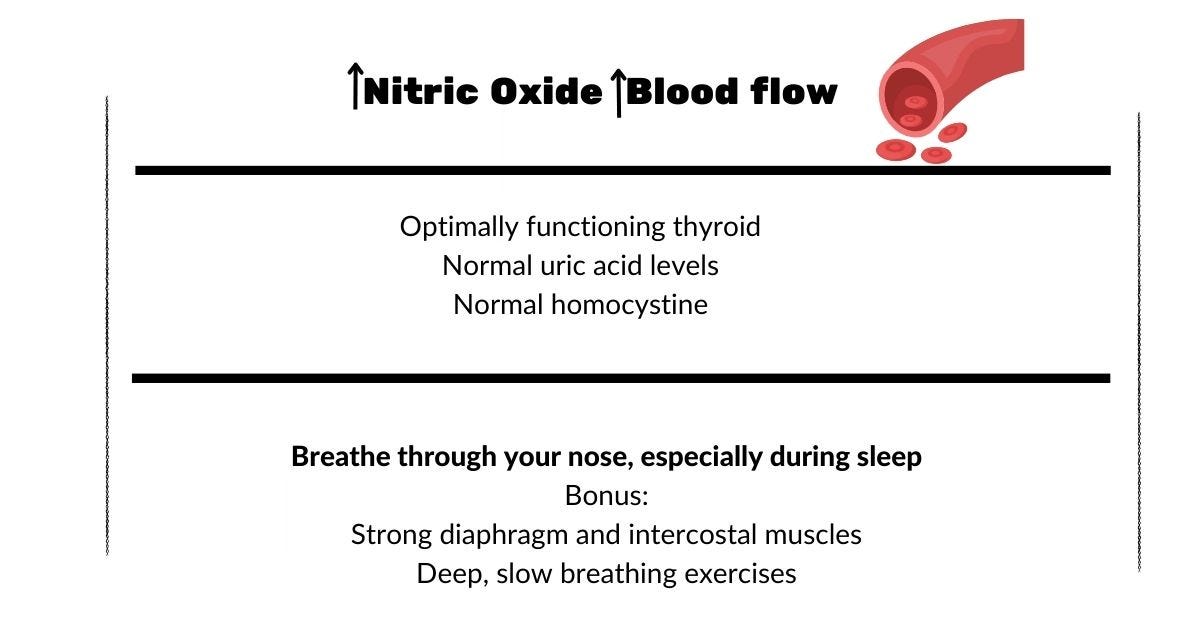

Dr. John Stamler professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and President, Harrington Discovery Institute has proposed that we have a three-gas system that involves nitric oxide in addition to oxygen and carbon dioxide. His 2015 study found that nitric oxide helps open up blood vessels in mice, allowing oxygen into tissues. Later studies confirmed this in humans as well. Stamler said this when interviewed about the study:

The simplified textbook view of two gases carried by hemoglobin is missing an essential element—nitric oxide—because blood flow to tissues is actually more important in most circumstances than how much oxygen is carried by hemoglobin. So the respiratory cycle is actually a three-gas system.

Because we don’t just need oxygen, we need good blood flow so oxygen and nutrients can reach our entire body. It’s like what happens when a food delivery person gets stuck in traffic. He has the food you ordered, but it’s taking too long to get to you.

For me, correcting iron deficiency helped, but it wasn't until I boosted nitric oxide that I really noticed a difference. But my research showed me there are these stumbling blocks that can get in the way.

Be aware of NO Blockers

There are three key factors that can cause nitric oxide to decline at midlife for women. Of course, estrogen and progesterone levels help stimulate nitric oxide where I talk about here. But I’m going to focus on three less known barriers.

First is declining thyroid function. A hypoactive thyroid will cause a decrease in nitric oxide production. It’s important to check your thyroid labs on a regular basis. Most importantly, is to make sure you’re getting enough of the key nutrients, especially iodine and selenium, which work together to aid thyroid function.

Next is homocysteine, a sulfur-containing amino acid, that rises during the menopause transition. When homocysteine is high (>10 mcmol/L), it can deactivate nitric oxide. Getting enough B vitamins and checking levels can help metabolize homocysteine to methionine, as explained in the post.

The last biomarker to monitor is uric acid. If this goes high (>5mg/dL) which tends to happen during menopause, it will also decrease nitric oxide. It also is linked to joint pain.

If you feel you are doing everything right and still feel fatigue, talk to your healthcare provider about these labs or consider private testing.

Check your breathing during Sleep

When James Nestor was researching his book Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art, he let Stanford researchers block his nostrils and breathed through his mouth for 10 days. His blood pressure shot up 13 points, he snored loudly, developed sleep apnea, and his oxygen levels dipped.

“We knew it wasn’t going to be good, because there’s a very firm scientific foundation showing all the deleterious effects of mouth breathing, from periodontal disease to metabolic disorders,” Nestor said in this CNN interview.

If you are making sleep a priority and still don’t feel rested after sleep, you’ll want to check for sleep disordered breathing (SDB). When there is higher resistance to airflow through the upper airway, it results in snoring and pauses in breathing..

As the body struggles to get oxygen, it periodically switches to mouth breathing. Signs include a dry mouth in the morning, frequent waking, and feeling tired even with enough hours of sleep.

This is important because it means not only do oxygen levels decline during sleep, but so does nitric oxide. This is because the nasal sinuses are a rich source of nitric oxide.

We often think of sleep apnea as a man’s disease, but risk goes up significantly around menopause. Approximately 20% of women develop SDB during the menopause transition. But even if you don’t develop sleep apnea, breathing through your mouth at night will negatively affect fatigue and health, decreasing the quality of sleep.

If you suspect you have an issue in this area, talk to your healthcare provider. I’ll be writing more about ways to enhance breathing during sleep, so stay tuned.

The Fatigue Formula

Although not the only cause of fatigue, looking at these hidden barriers can help you find answers. That’s because your body needs sufficient oxygen, a way to transport it, and optimal blood flow, what I call the fatigue formula.

Red blood cell health: Ensure optimal iron, B12 and folic acid for red blood cell formation and oxygen transport

Sufficient nitric oxide: Be aware of potential blockers to good blood flow, and keep them under control.

Breathe right: Avoid mouth breathing, especially at night for good blood flow and oxygen levels.

Midlife women should never accept fatigue as the norm. I know I never will again. What has been your experience with fatigue at midlife?