Why are we neglecting thyroid health in women over 40?

I’m digging into thyroid dysfunction and why midlife women are at heightened risk

I never thought about thyroid health until midlife. Not only have several of my friends had issues, but I keep bumping up against it in the research.

I recently read a study with Indian women over 40, where almost half had some type of thyroid dysfunction. Thirteen percent had hypothyroid, 23% subclinical hypothyroidism, 3% hyperthyroid, and 7% subclinical hyperthyroidism.

Not only that. Women are 5-20 times more likely to develop a thyroid disorder than men. There is clearly something going on at midlife with women and their thyroids.

And I want to spend some time digging into not only why this is but the health implications and what we all can do about it.

Thyroid 101

Shaped like a butterfly, the thyroid gland is located beneath the Adam's apple in the front of the neck. Specialized cells in the thyroid are especially good at extracting iodine needed to make thyroid hormone.

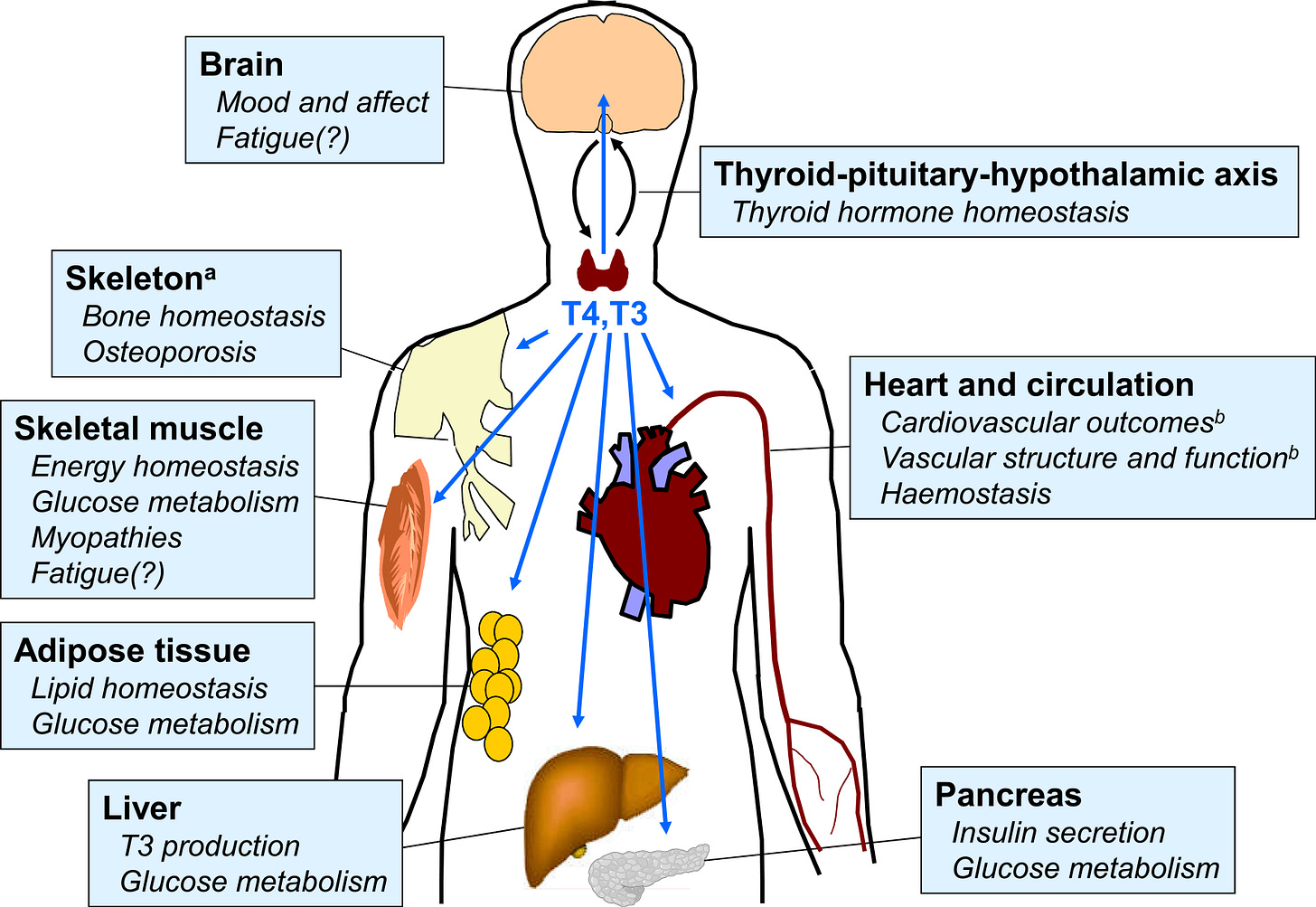

The production of thyroid hormone is based on a feedback loop in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. When thyroid hormones decrease, the hypothalamus releases thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), causing the pituitary gland to release thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

TSH stimulates the release of the thyroid hormones, triiodothyronine (T3) and tetraiodothyronine (T4). The active form of thyroid is T3, which is produced through deiodination of T4.

As T4 and T3 rise, they exert negative feedback on the pituitary which decreases TSH secretion. Scientists refer to this feedback loop as the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis (HPT).

Over 99% of thyroid hormone is bound to thyroid-binding globulin (TBG), albumin and prealbumin. This means only about 1% of thyroid hormones are free to attach to thyroid receptors and do their job.

As you can see below, thyroid hormones help with the functioning of the heart, glucose metabolism, muscle, bone, and the brain. But for midlife women, something happens increasing the risk of thyroid dysfunction. And here’s why it matters.

Lab values

Thyroid problems are classified as either hypothyroidism, low hormone levels, or hyperthyroidism, excessive hormone production. When you have low thyroid function, TSH levels rise to stimulate more thyroid hormone. Yet with overproduction of thyroid hormone during hyperthyroidism, there are lower levels of TSH function.

Overt hypothyroidism (TSH >10 mUL and low FT4) is most often associated with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, an immune condition that attacks the thyroid affecting .3- 3.7% of the population. Grave’s disease is the autoimmune condition frequently behind hyperthyroidism affecting 2% of the population (<.1-.4 mUL).

Immune causes of thyroid dysfunction typically have high levels of antibodies to thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO).

What’s even more common is subclinical hypothyroidism, affecting 12% of the population, when the TSH is >4-4.5 mUL. Since the early 2000s, there has been much debate on whether to lower TSH levels that make up normal thyroid function, with levels as low as 2.5-3 mUL being proposed.

Let’s consider the health implications of different thyroid markers before digging into what is happening in midlife.

Heart health implications

We've known for a long time now that there is an inextricable link between thyroid health and heart health. According to a 2019 review in Circulation:

The effects of thyroid dysfunction on the cardiovascular system have been well documented for >2 centuries. Clinically, both thyroid hormone excess and deficiency can induce or exacerbate cardiovascular disorders, including atrial and ventricular arrhythmias, atherosclerotic vascular disease, dyslipidemia, and heart failure.

Research is showing that thyroid status that is low-normal thyroid function (which means a TSH inching up) may compromise heart health, too. In one study, women in the lower most quartile for Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH, 0.3–1.44 mIU/L), were less likely to have metabolic syndrome than those in the upper quartile (TSH, 2.48–4.00 mIU/L). Another study with postmenopausal women found that a higher TSH was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease when compared to healthy women with TSH levels within the normal range.

The Norwegian HUNT study followed people without thyroid dysfunction for 11 years and found that those with increasing TSH had higher blood pressure, cholesterol, triglycerides and decreasing HDL.

Yet we are all different and evidence is pointing to individual set points at thyroid levels, as stated in this 2015 review in Nutrients:

Since each individual probably has a narrow set-point of thyroid function status [8], the concept is now emerging that low-normal thyroid, i.e., higher TSH and/or lower free thyroid hormone levels within the euthyroid reference range, even when determined at a single time-point, could have a negative impact on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Several potential mechanisms explaining the thyroid heart-health condition have been proposed including changes in lipid metabolism. Additionally, both myocardial and vascular endothelial cells contain TSH receptors and higher TSH reduces the endothelium’s ability to make nitric oxide, which helps keep arteries nice and flexible. This also increases inflammation/oxidative stress, thus negatively affecting the One Health Principle.

But why or why is this more likely to happen to us along with everything else in midlife?

Aging pause and the thyroid

There are a variety of reasons thyroid function can become compromised at midlife. First is the body’s decreased uptake of iodine.

Aging induces thyroid epithelium degenerative processes, leading to its flattening and reduced size, decreasing the uptake of iodine. For instance, people over 80 have reduced ability to uptake iodine by 40% compared to someone 30 years old. Because this is likely a gradual process, it’s possible that people's ability to uptake iodine is already somewhat compromised by midlife.

As women enter the late reproductive stage and perimenopause, things get even more interesting. The relationship between Hypothalamic Pituitary Gonad (HPG) and (HPT) is reciprocal, as the thyroid contains estrogen receptors and the ovary contains thyroid receptors.

Thyroid hormones affect reproductive function and estrogen increases thyroxine binding globulin (TBG), lowering the concentration of free hormone. (del Ghiranda)

Animal studies have shown that removing ovaries reduces thyroid hormones T3 and T4, yet researchers have not found hormone therapy to be helpful for thyroid function and it may even worsen thyroid function.

A few things could be happening. Fluctuations in estrogen and eventual lowering of it could cause dysregulation in the pituitary secretion of TSH (Slopien). In a study looking at TSH levels in pre and postmenopausal women, TSH was higher (3.39 vs. 2.6) in postmenopause while T4 and T3 were unchanged.

When given high doses of estradiol, only the younger rats took up more iodine while the older rats given the same dose did not. Maybe the role of aging is why higher estrogen levels can no longer stimulate iodine uptake.

I’m not trying to oversimplify this complex area. But I can’t help but wonder if women experience more thyroid dysfunction (compared to men) because of the “second hit”of hormone changes. It's like the reason they warn against playing after a concussion. A second hit will do a lot more damage.

Complicating matters is it is hard to distinguish thyroid symptoms from menopause symptoms.

Symptom overlap

There is much overlap between menopause and thyroid function. First, the influence of thyroid hormones on brain function is similar to estrogen and has been associated with depression and insomnia.

In one study, researchers were looking for the relationship between thyroid hormones, menopause, and various symptoms in 202 women aged 42-65. These researchers propose low estrogen as a trigger for thyroid related symptoms, especially nervousness.

We think that the increased influence of thyroid status on nervousness in menopausal women is directly triggered by loss of estrogen.

They did not find a link between estrogen levels and thyroid status. What's important to remember is that changes in the thyroid, possibly influenced by estrogen, could be linked to the symptoms women experience.

In my quest to find answers, I couldn’t help but consider how nutrition may help women sustain this “second hit.” Particularly micro-nutrition.

Micronutrients’ role in thyroid health

I’m always drawn to the fact that micronutrients are vital for thyroid health. First and foremost is iodine. This is especially important given urinary iodine levels have decreased 50% since 1970.

Iodine excess can cause an immune response in certain individuals. Yet, studies have shown that selenium, a potent antioxidant, reduces TPO-antibodies and provides protection against any damage that could occur due to iodine.

In one study, researchers gave 83mcg of selenium to 196 people with autoimmune thyroiditis, and 17% of them experienced restored thyroid function. If we have an excess of iodine but insufficient selenium, problems can arise.

Another factor is magnesium can affect iodine uptake by thyroid cells. So, if magnesium levels are low, that can also affect the thyroid through its relationship with iodine.

We also need TPO to make thyroid hormones. Iron is a cofactor in the production of TPO. Research suggests that iron deficiency is associated with an increased risk of positive thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) in women of reproductive age and the development of subclinical clinical hypothyroidism in pregnant women.

Adequate vitamin D status helps in keeping the immune system from going haywire and researchers have linked low levels to autoimmune thyroiditis. In almost all the randomized control studies to date, vitamin D supplementation has helped significantly lower anti-thyroid antibody (TPOAb and TgAb) levels.

And even when we can make thyroid hormone, the body needs to convert T4 to the active form T3. And selenium and zinc are involved in these reactions.

But that’s not all. A study in the 2021 Journal of Thyroid Research set out to discover how over 30 micronutrients affect thyroid markers in 387 healthy people, by testing blood levels and figuring who is deficient, normal and in excess.

They found that low levels of riboflavin, vitamin B12, folate, and vitamin D significantly affected thyroid functioning. And levels of free T3 showed a correlation with calcium, copper, choline, iron, and zinc. Several amino acids also played a protective role in thyroid health. The researchers make the following conclusion:

The present study concludes that deficiency in essential micronutrients results in extreme derangement in thyroid functioning. The study also highlights the importance of serum levels of certain amino acids such as asparagine, serine, valine, leucine, and arginine are related to thyroid functioning. However, further detailed investigations are required to evaluate the physiological importance of these findings

This is why micronutrients and thyroid function are difficult to study–there’s a whole slew of them that play a role.

So what can we do?

Midlife women benefit from tracking their thyroid biomarkers and talking to your healthcare provider about symptoms and levels.

As I mentioned in my Biomarker Guide (all subscribers get it), if you have a TSH inching up, you can ask your doctor for an anti-TPO lab, which will help determine if there's an autoimmune issue brewing. If you are TPO positive, consider seeing an endocrinologist who has knowledge about thyroid dysfunction.

Tread carefully. A 2018 study in Thyroid found that there is an overuse of levothyroxine replacement. When 291 patients (>80% female average age 48) stopped their thyroid medication for 6-8 weeks, 61% became euthyroid (normal). It’s advisable to get a second opinion if you feel you're being put on medication too soon.

Additionally, as we navigate through post menopause, excessively suppressing TSH with medication may also have negative consequences, considering the shifting effects of thyroid function in older age.

I can't help but wonder if optimizing micronutrients that support thyroid health would improve the 'second hit' of perimenopause and menopause. It would be an interesting study, don't you think?

Every midlife woman needs to be sure she’s getting key micronutrients and not in excess either. Right around or a bit more of the RDA for iodine through a multi or drops like Mary’s. Selenium and zinc through diet and a multi. Get tested for vitamin D, iron, and vitamin B12 because we all absorb these differently and diet is not a good indicator.

Why do we accept the fact that so many midlife women encounter declining thyroid function? And shouldn’t we consider thyroid health when they are nervous/anxious, have palpitations or their blood pressure rises and cholesterol spikes up? Where are the studies digging deeper into this?

This heart health month, remember that your thyroid plays a part in helping keep your heart healthy.

Any midlife thyroid stories to share?

Here are some posts for further reading:

Yes, every midlife woman should take a multivitamin (and here’s why)

The invisible epidemic of iodine deficiency

Ferritin: the blood test everyone women should get at every doctor’s visit

7 foods every women over 40 should be eating

As always, this information is to educate you and not replace medical advice.

I am saving this post! So much good information that clearly explains the details surrounding thyroid function especially in regards to aging. Great information to help women understand how thyroid issues and menopause issues can overlap. Thank you!!

Yes yes YES!! I have been dealing with subclinical hypothyroidism for a few years now after having it under diagnosed for many years by docs (apparently very common in women after childbirth). It took a naturopath to see my tsh of 2.3 combined with my symptoms of fatigue and brain fog to treat me with natural bovine hormone. I interviewed a handful of docs and endocrinologists who subsequently refused to treat me because my labs weren’t severe. This has opened my perspective to naturopathy but also opened me up to many hucksters who claim to have the best thyroid diet or supplement or whatever.

Now I’m struggling with drastically increased ldl levels after never having high cholesterol but am thankful to you Maryann bc now I know thyroid (and perimenopause) may well be behind this.

Keep up the good work! Another site I consult with constantly is called “stop the thyroid madness”.