Where is the midlife woman's Rose Frisch?

In the 1970s, pioneer research Rose Frisch made the connection between adequate body fat and fertility. Midlife women desperately need a researcher to define midlife body fat changes.

In the 1970s, pioneer researcher Rose Frisch made the connection between a female’s body fat and the start of menstruation. Frisch discovered that a female body won’t ovulate if it thinks a girl or woman doesn’t have enough fat reserves (>17%) to support a pregnancy.

Although her fellow researchers balked at the idea at first, this led to the discovery of fat as an endocrine organ that secretes hormones called adipokines. One of those hormones, leptin, sends a message to the command center of the brain, the hypothalamus, about how much body fat a person has.

Most of the fat in the young woman's body is subcutaneous, not visceral. In fact, at this stage, fat is more often stored in the legs, hip, and buttocks area. It has been proposed that fat stored in this area is a superior source of DHA, which is of significant benefit to a potential baby.

Regardless, we now know the importance of body fat for women. But as we get older, this isn’t the case.

We often hear that perimenopause is puberty in reverse. That’s because instead of hormones going up, they are declining. Well, not at first. It’s more erratic and progesterone declines first. You can read more about that here.

And like puberty, midlife women gain weight, but researchers attribute this to aging and not menopause. But the decline in sex hormones increases body fat and decreases lean body mass. And most of this transition occurs during perimenopause.

For instance, a cross-sectional study with 72 women ages 35 to 60 years was evaluated body composition. Those in perimenopause had 16% higher body fat compared to premenopausal women and 5% higher than post-menopausal women. They also had 6.1kg lower lean mass compared to the premenopausal women.

This shouldn’t be surprising, as during early perimenopause, estrogen is still high, but progesterone is low. This occurs during puberty when girls gain body fat. Although they eventually get their periods, according to Jerilynn Prior at Cemcor, they don’t have predictable ovulation for 12 years, which means they have likely have high estrogen and low (or lower) progesterone.

During the menopause transition—mainly due to losses in estrogen — fat not only increases but it is preferentially stored in the midsection instead of the butt and thighs. Regardless of changes in weight, women in this stage have higher body fat and visceral fat (deep in the abdomen) than premenstrual women.

This is where alarm bells ring because visceral fat is known to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines having adverse effects on health if it gets too high (we need some visceral fat, after all). To give you an idea, the average midlife woman’s visceral fat increases from 5-8% premenopausal to 15-20% after menopause.

Yet only 25% of the visceral fat gains are from gaining weight when just as much (25%) comes from losing muscle and about 50% is from fat redistribution of fat during perimenopause/menopause. It’s important to note that body fat in your midsection is not automatically visceral fat—in fact, 85% is subcutaneous.

We’re all screwed, right? Not so fast.

Could body fat changes be protective?

Thanks to Rose Frisch, some fifty-odd years later, the gain in body fat at puberty and the need to keep it above 17% for pregnancy, is common knowledge. It’s written in textbooks, fertility resources, and puberty books for girls. Yet the body changes in midlife are not so well defined.

But if I’ve learned anything, it’s that when many people in a group go through something that is seemingly bad, the body is doing it for a reason. And it’s important to note that unlike puberty, midlife women are also aging.

And as we age, the body accumulates fat stores until about 60 years of age, where it begins to decline. Nobody escapes body fat increases with age. This is even true in trained athletes who have their body composition checked over many years. Their fat mass increases even though it is still considerably less than someone the same age who is sedentary.

Emerging research shows that body fat is protective or neutral in women as they age. In a 2021 study in Journal of American Heart Association, researchers examined national health survey data in over 11,000 individuals. In the group, 5627 were female and half were over 50. Women with high muscle mass and high fat, had a 42% reduction in heart disease than the low muscle and low body fat group. This surpassed women with high muscle mass and low body fat.

In a 2022 study, midlife and older women and men had body composition and heart function tested. Lean body mass in women was linked to stronger heart function in women, but not men. Not only that, but body fat mass had no effect on heart function.

According to a UCLA press release on the 2021 Journal of American Heart Association study:

The research also underscores the need to develop sex‐appropriate guidelines with respect to exercise and nutrition as preventive strategies against the development of cardiovascular disease. Even with the current emphasis by health experts on reducing fat to lower disease risk, it may be important for women to focus more on building muscle mass than losing weight, the study authors say.

Fat can be healthy (or not)

Conventional wisdom tells us that when we gain weight, fat cells increase in size (hypertrophy). Hypertrophic fat cells can get stiff, affecting membrane signaling, which sets off the secretion of pro-inflammatory adipokines, which, as we’ve already mentioned, happens to a greater degree in visceral fat.

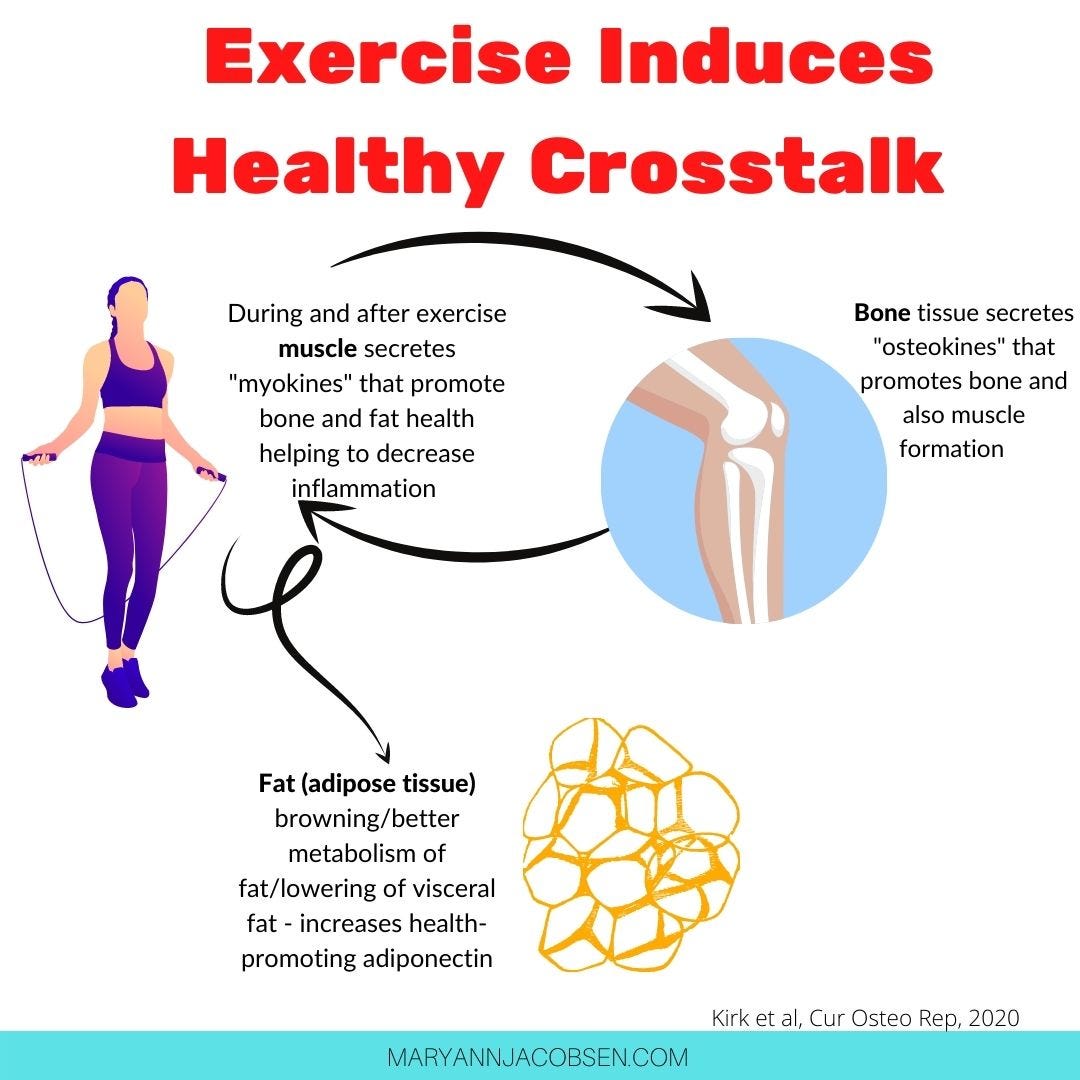

Although this can happen, the caveat is that much of these negative effects comes from the negative crosstalk from inactive skeletal muscle and bone and can happen even if we don’t gain weight.

When, on the other hand, fat receives positive crosstalk from active muscle and bone, it becomes healthier. In short: exercise builds up muscle and bone, decreases the amount of visceral fat, increases the browning of fat, and helps mitochondria in fat become more functional.

In a 2021 review of over 200 studies, Gaesser and Siddhartha found that exercise improved health outcomes much more than weight loss did.

“Compared head-to-head, the magnitude of benefit was far greater from improving fitness than from losing weight,” Dr. Gaesser said in a NY Times interview. “It looks like exercise makes fat more fit.”

So could it be that exercise is key to keeping visceral fat down, fat healthy, lean body mass up, and bones strong in women with aging and hormonal changes?

Show me the research

Personally, I’m tired of all the bad news us midlife women receive about our changing bodies. Isn’t it time we did the research needed to help women understand these changes and nurture their bodies?

Some reasons body fat increases at midlife include fat as a source of estrogen. Perhaps the body is working out how much it needs to function postmenopause? Could it also be that midsection fat stores are more efficient at generating estrogen?

It's also a way to counteract losses in muscle mass, as I describe here. Additionally, fat tissue is a source of adiponectin, an adipokine found vital in extreme old age and one that increases nitric oxide, the magic midlife molecule. Body fat also keeps us warm and protects our organs.

Here's the thing. Developmental stages always make humans vulnerable, and midlife is no different. But women at this stage deserve so much more than what they are getting.

I’d love to see a researcher, like Rose Frisch, find answers to why body fat changes at midlife and beyond, so we can stop guessing.

Will the next Rose Frisch please stand up? I, for one, will welcome this person with open arms.

Anyone with me?

PS Apologies for typo! 😬

This is fascinating thank you. I have just started reading research by Danish researcher, Dr Susanna Soeberg on the effects of cold and heat on brown fat. This is such a new way of looking at fat for me. I think fart has long been given bad rap and it's so helpful to reframe it.