An in-depth guide on midlife weight gain: Everything you need to know

Weight and body composition changes, explained

I don’t weigh myself often. Usually at doctor visits and sometimes at the gym. But during my recent doctor visit, I had gained more weight than what was usual for me. And I thought it was something I should talk about.

Weight is a sticky topic these days, making it difficult to write about. But I hope by sharing my experience, I can help other women understand their changing bodies.

I think there’s a lot missing in the weight conversation at midlife. That’s partly because the thinking on this subject has become so polarized and innovative research is lacking. But we can piece together the data and make decisions that work for each of us.

So, let’s do this by rewinding to the beginning of my midlife body changes. Skip this one if you have a history of eating disorders or are going through a difficult time.

Early midlife body change: Pregnancy aftermath

As I entered midlife, I had just had my second baby. Three days before my 40th birthday, to be exact.

When I finally came up for air, my weight after kids (and at the start of midlife) was roughly 10 pounds higher than what it was in my 20s and early 30s.

I concluded that this was where my body wanted to be as I write about here. Eventually, I came across the book "Why Women Need Fat" and the authors' theory of weight gain for women in adulthood, written by William Lassek, MD and Steven Gaulin, intrigued me.

According to the authors, women typically reach their lowest weight prior to having children. But with each additional pregnancy, women gain extra weight, mostly in the waist. They also say that women who don’t become pregnant see an uptick in weight around age 36. Here’s a snippet:

“A girl stores fat through her childhood in her legs and hips to bank the omega-3 DHA that her children will need in order to have a large and well-functioning brain. But her waist fat remains limited, to lower her chances of having a first baby that is too big to be born or of developing preeclampsia. Gaining weight after having her first baby is beneficial for any other babies that follow. So if she has food available, she needs to gain more weight so that her children will be able to take full advantage of living in a world where food is plentiful.”

Thanks to researcher Rose Frisch, it’s common knowledge that girls gain weight and body fat at puberty to prepare for their menstrual cycle. And of course, women gain weight with pregnancy. Besides that, we have little knowledge about the changes in women's bodies as they age. Instead, it’s all made out to be doom and gloom.

Further into midlife: Less body movement

Somewhere in my mid-forties, I noticed gradual weight gain—one to two pounds - each time I went to the doctor’s office. When this happens, I do a quick regulation check. It’s what I call the why behind the weight.

If my body changes, I look at factors that affect how I regulate food, such as stress, emotional health, sleep, diet quality, eating in the absence of hunger, and physical activity. Then it hit me. I always did structured exercise but soon realized I no longer moved my body as much.

I quit my 3-day week hospital job which gave my body a lot of movement. So, I started my regular walks and my weight inched back down. I continue these walks to this day.

This regulation check isn’t just about weight gain, but about any body change. When I had severe anxiety in my 40s a few years later, my weight dropped. I knew it was due to swallowing problems from the anxiety because it happened to me before.

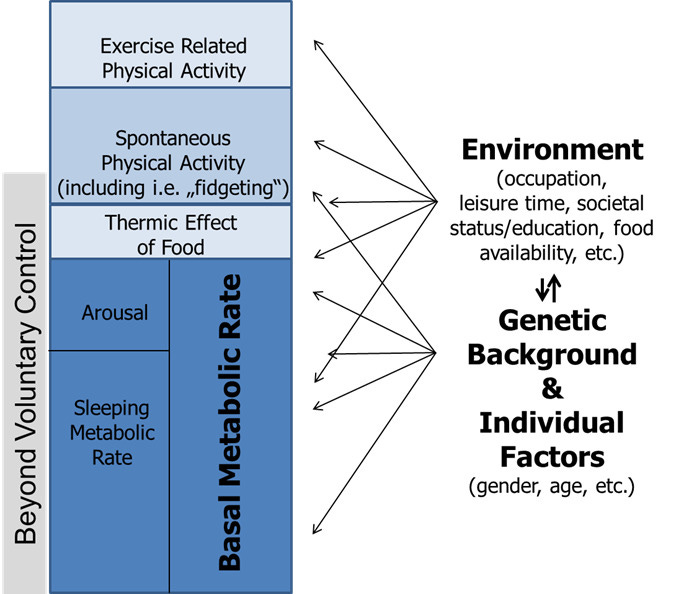

The Monet study, which looked at energy expenditure during the menopause transition, found that midlife weight gain was more often the consequence of reduced activity than increased calorie consumption. On a population level, the structured exercise we do does not affect energy expenditure as much as something called nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT). I say “population” because individually this may be different for, say, a long-distance runner. The chart below shows the contribution of NEAT.

This was what was happening to me. I would go to my workout class and sit the rest of the day. My NEAT had decreased considerably. This can happen when we change something in our life, like jobs, working at home for more days, becoming a stay-at-home parent, retiring, etc.

I started to walk around the block at my complex for writing breaks. When the kids were playing in the park, I’d walk. During games and practices, I’d walk. Now that my kids are older, regular walks are part of my day and they help me work out ideas or just enjoy a podcast. Walking outside also helps me get adequate daylight.

“NEAT comprises the largest share of daily activity-related thermogenesis, including for most subjects engaging in regular physical training. It is important to note that both NEAT and spontaneous physical activity are not interchangeable but represent complementary concepts.”

-Christian von Loeffelholz, MD and Andreas L. Birkenfeld, MD

Lean body mass decline (and fluctuations)

After 30, populations gradually lose lean body mass if they don’t consume adequate protein and exercise. This is because before 30, the body uses growth hormones and insulin to build lean body mass. But after 30, it happens through the branched chained amino acid (leucine) trigger according to researcher Donald Layman.

One theory presented in this study describes how the body reacts to losses in lean body mass. In order to hold on to lean body mass, the brain increases hunger, which can add body fat and keep lean body mass (by weight) stable.

Trying to lose weight conventionally may have unintended consequences. Research shows that quick weight loss induces both losses in fat and lean body mass. With this type of intentional weight loss, for every pound of fat lost, roughly a quarter of it would be lean body mass. And we can also lose bone density in the process.

Now this may not be true if you up the protein and do weightlifting, but researchers know little about how this affects individual women as they age and have reductions in sex hormones.

If we gain the weight back, which often happens, increased hunger remains until the body recovers the lean mass. By the time someone recovers their muscle, they have more body fat than when they started. This is called “fat overshoot” and has more of an effect on leaner people.

But if a woman is older than 60, doesn’t exercise or have an inadequate diet, she may not recover the muscle loss. A study in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition uses the term “collateral fattening—a process whereby excess fat is deposited as a result of the body’s attempt to counter a deficit in lean mass through overeating.”

Lean body mass is vitally important as we age, and the body works to spare it anyway it can. And because fat helps spare protein, it accompanies the ride to ensure less loss.

Something being studied right now that builds off this theory is the Protein Leverage Effect. The general idea: as the body loses bodily protein during midlife, appetite increases. In short, appetite will elevate until a person meets these protein needs. The researchers suggest that increasing protein can offset these changes:

increases in dietary protein concentration in the range revealed by our analysis (around 1–3% DE) may not only address the problem of increased energy intake but also, at least partially, overcome anabolic resistance and restore lean tissue masses. As anabolic resistance worsens with advancing age, further increases in protein intake may be required.

They propose a four-year study, so we’ll see if we get more data here. I don’t believe this is the only reason bodies change during midlife: it’s also about hormones.

Here comes perimenopause

The hormonal changes of perimenopause and menopause alter body composition, including increasing body fat, visceral fat (deep in the abdomen), declining muscle mass, and bone loss closer to and following menopause. But the biggest change happens in perimenopause.

I’m 54 and still haven’t gone a year without a period, which is considered menopause. Right before I turned 53, I experienced an uptick in my weight. This wasn’t the gradual 1 to 2 pounds a year but an 8ish pound increase.

And I finally did something I hadn’t done until this point. I got a DEXA scan. I just wanted to know if perhaps this gain was all muscle (ha, ha). After all, I've made weight training more of a focus since turning 50 and my clothes fit the same.

When the report was handed to me, I didn't quite know how to react to a body fat percentage of 34%. This seemed high, but again, what did I know? My visceral fat measured below cutoffs, and I was in 99 percentile for bone density for my age. And my relative muscle mass index was above their cutoff.

There is surprisingly little research on health links to body fat percentages and lean body mass as we get older. If you go to a gym, they often count anything over 30% as problematic. But according to the research this DEXA company used, their cutoffs were 39.9% for women 50-84 years old.

A study back in 2019 was the first to look at body composition changes during the menopause transition. While there were fat mass increases premenopause, they multiplied by 2 to 4-fold during the transition. Lean body mass also decreased by 1.9% while fat mass increased 3.6%. After menopause, the slope went back to 0.

Interestingly, Chinese and Japanese midlife women did not experience this change in body composition like whites and blacks did, showing differences based on ethnicity.

A 2022 cross sectional study of women during the menopause transition found perimenopause is a time of profound change. In perimenopause, women had higher body fat by 10% compared to premenopause and 1.2% higher than postmenopausal women. Women in perimenopause experience an increase in fat and lower lean body mass compared to pre and post menopause:

“measures of fat distribution indicated that PERI women experienced comparatively greater fat deposition in the abdominal region, with AG ratio in PERI being on average 16% higher than PRE and 5% higher than POST, with similar differences for VAT.”

Other studies show that women lose about 11 to 13 pounds of lean body mass throughout their premenopause to post menopause journey. In short, a lot goes down in perimenopause. It’s important to note that changes in body weight do not always occur.

I’m guessing that these changes happen during perimenopause when hormones are declining, especially estrogen. Because body fat is a source of estrogen after menopause, the body may be in overdrive to ensure women can make enough estrogen without help from the ovaries. Then once menopause hits, it can relax a bit.

I was curious if this was my body’s way of asking me to build more muscle. So that’s what I tried to do.

Adding protein and lifting heavier

I was already roughly aiming for 30 grams of protein at meals but decided to increase protein at breakfast and lunch, including sources of leucine known to trigger muscle protein synthesis. I also picked up heavier weights at my bootcamp workouts.

As I approached my upcoming doctor’s appointment, my weight had returned to its general baseline. I went back to get the DEXA to find that yes; I lost fat, but I also lost 2 pounds of lean body mass. And my weight loss was not intentional. Well, I thought, this isn’t good.

I wondered if I had a particularly tough time building lean body mass, and therefore could lose it easily. One’s ability to build muscle and strength is 50-80% genetic, according to one study. I moved from a bootcamp gym to a gym that exclusively focuses on strength and really helps with form. We also record how much we lift and aim for progressive overload.

There isn’t much cardio, but I still run and do other forms of aerobic training outside of this class. My aim was to train there 3 times a week and do one on my own. For the first time, I felt like I gained more strength, and it was fun to see my numbers go up, even if it was just 2.5 pounds. I also had solid form, something that had been missing.

I’m still in awe of women who can lift a lot more than me, but I realize I need to focus on myself and my gains, no matter how small. At my most recent doctor's appointment, my weight jumped back up, and I got another DEXA.

But this time I gained 4.5 pounds of lean body mass! Yes, I also gained just as much body fat, but given that women typically lose lean body mass at my stage, I was happy. Plus, my metabolic health had not changed. If anything, it had improved.

We need to stop generalizing about body fat

Since researching midlife, I’ve discovered two things we need to talk about more. And that’s the functioning and health of our body fat, and where it’s stored. Although it’s easy to focus on a magical body fat percentage, not all body fat is created equal.

Exercise and diet quality help fat function better but also make it less likely to be stored in the viscera, deep in the abdomen. Researchers suggest this type of fat in midlife women is linked to metabolic dysfunction where subcutaneous fat is not.

In one study with men (sorry), exercisers had better and healthier functioning fat. Researchers at Stanford University School of Medicine found that omega-3 fatty acids help a person have more insulin-sensitive fat cells, which is healthier than insulin-insensitive bigger fat cells.

This may also be why studies on weight and health outcomes with aging are so mixed—some showing benefit and others detriment.

Physical activity plays a key role here. Rodents bred for high levels of physical activity were protected against metabolic dysfunction following ovariectomy, but those with low fitness were not. A thoughtful review on the subject puts it this way:

“It is not excess fat per se that is metabolically harmful; when functioning properly, fat protects other organs, such as liver tissues, from ectopic lipid deposition.”… Exercise is particularly effective at reducing visceral fat and thus critical in mitigating the accumulation of visceral fat during the menopause. In addition to facilitating fat loss, exercise is also likely to improve fat cell metabolism and may be effective in “replacing” the beneficial effects of estrogen.”

And here’s the whopper. It takes 8-10 years to replace fat cells. If we stick with healthy habits long enough, we can transform our fat. Plus, fat, muscle, and bone talk to each other. And when we partake in exercise, they secrete cytokines that improve the health of each other.

My ultimate decision to trust my body

Although I always get curious about weight shifts, and make changes as needed, I trust my body knows what it’s doing. That means I’m not attempting to lose body fat, especially during perimenopause when my body is figuring things out. But I’m going to keep at my strength training, aiming to get my body stronger, adding any lean mass I can.

Yet we are all different - genetically, ethnically, and personally. You may have a very different story and might make a very different decision. And that’s okay.

This reminds me of something journalist Taffy Brodesser-Akner wrote this 2017 viral NY Times article, “Losing it in the Anti-Dieting Age:”

“Even in our attempts to free one another, we were still trying to tell one another what to want and what to do. It is terrible to tell people to try to be thinner; it is also terrible to tell them that wanting to lose weight is hopeless and wrong.”

No matter what you do, here are important tidbits to remember:

We are likely not meant to be at the same weight as we age

Children have growth curves to check if their growth is on track. But for adults, we just paint a negative picture instead of trying to make sense of changes. It seems most of us (67% in a study) will gain weight throughout midlife. This is not bad per se, but likely is a part of our continued development. And yes, like all developmental stages, this can make us vulnerable.

Yet not everyone will gain weight, some may lose, and others may fluctuate. Understanding the why behind it can be helpful in deciding what, if anything, we should do.

Always remember population vs. individual

Researchers look at large populations of people and make determinants. Even if we generalize about body changes in midlife, we all have our individual experiences. For instance, our ethnicity can affect this, as can our genes and lifestyle.

Genetically, some women naturally hold on to lean body mass more than others. Others may gain more body fat at midlife.

According to overfeeding studies, there are huge variations in how individuals respond, with some gaining more weight than others. And that big, publicized study showing that metabolism doesn’t slow at midlife, also revealed large variations in metabolic rates.

It’s hard not to compare ourselves to others, especially in the social media age, but we need to learn about our own body and make decisions that work for us.

Perimenopause and menopause results in body composition changes for most women

Perimenopause is defined as a change in the menstrual cycle by 7 days (early peri) and a missed cycle by 60 days (late peri) is the most profound time of changes in body fat and lean body mass. Bone loss occurs closer to menopause and post menopause.

In the nutrition world, I feel like we’ve learned not to generalize about carbs, protein, and fat. For instance, a piece of cake differs from a serving of quinoa, and the same is true for our own body. Just knowing a body fat percentage is not the complete story, as what matters is fat functioning and where it's stored.

Exercise—both aerobic and strength training—is a midlife woman’s best friend. It helps the health of our muscles, body fat, and bones. And it makes us feel better every single day.

Also, don’t forget about declines in NEAT that often happen in midlife. Moving throughout the day—in addition to structured exercise — is important. Not only that, but “walk breaks” aids blood sugar control.

If we lose weight, gradual is better and looking at underlying culprits will be most sustainable.

At midlife, weight loss should not be taken lightly. Weight loss, especially when done quickly, can decrease lean body mass and enhance bone loss. And weight cycling can negatively affect cardiovascular health and result in fat overshoots.

Yet gradual weight loss is linked with better outcomes. Looking at contributing factors and tackling underlying causes seems to make the most sense. If calorie deficits are followed (including intermittent fasting, which reduces calories), it’s even more important to increase protein and participate in weight training.

Conclusion

We still have so much to learn about why and how women’s bodies change in midlife. It’s complicated and not something that can't be tied up in a neat little bow for the masses. We certainly need more research and insight.

What I know for sure is that we are all not meant to be one size or leanness and that healthy can look differently for different people. Although we have key principles that apply to most, what we do within those principles will vary. And that’s okay. We are not populations, but individuals, and should be treated that way.

I’d love to hear your story and experience with body and weight changes at midlife in the comments, or by replying to this email.

Thanks so much for all your work on this Maryann. So interesting and helpful!

More weight may be protective after menopause. See this book: https://www.amazon.com/Obesity-Paradox-Thinner-Heavier-Healthier/dp/1469090953