Why staying hydrated gets tougher in midlife—and what to do about it

Another piece to the midlife health puzzle: optimal hydration

I started collecting clues I wasn’t hydrated.

Sometimes when standing after sitting, I get a little dizzy.

I could go long periods without going to the bathroom and rarely got up to go in the middle of the night like I used to.

I really wasn’t thirsty that often, despite the hot summer we were having.

While conducting my research, I've come across snippets of information about midlife hydration but haven't delved into it yet. I had also heard that with aging thirst is less reliable.

These new clues were the push I needed to focus on hydration both in my research and real life.

So, join me, as I once again search for answers about the unique needs of midlife women. Let’s start by going back a couple of decades.

The 8X8 controversy

Throughout my career as a dietitian, no health advice was given more frequently than "Drink eight 8-ounce glasses of water per day."

It wasn’t just dietitians giving this advice, but doctors, nurses, coaches, trainers, and friends, too. Basically, anyone vaguely interested in health!

For me, the water craze turned upside down in the early 2000s when two events happened. First, I started hearing reports of water intoxication - including some deaths - in marathoners. As a marathoner myself, this was a little scary.

In 2002 Valtin reviewed the evidence to find there were surprisingly no studies to support this recommendation. He also challenged the idea that beverages like coffee, tea, and alcohol don’t count towards total fluid intake:

I have found no scientific proof that we must “drink at least eight glasses of water a day,” nor proof, it must be admitted, that drinking less does absolutely no harm.

This is about the time I backed off drinking water all day and followed my thirst. I still had water with me, especially during workouts, but I no longer tried to drink more on purpose.

It has been 22 years since Valtin's bombshell article, and I wanted to review some new studies.

But first, let’s start with the importance of water and fluid balance for our bodies.

The importance of water and fluid balance

Water is the largest component of the human body registering at about 40-62% of our body’s mass. In women, the body loses 2.8- 3.3 liters per day through respiratory, fecal, urinary and perspiration losses. Because the body can only make a small amount of water, we need to replace the losses.

In the body, water aids metabolic function, regulates body temperature, and ensures muscle function and quality. It also helps remove waste, enables nutrient transport, and protects organs.

Water acts to lubricate the mouth (saliva), eyes (tears), and joints (synovial fluid) and promotes mucous membrane cleansing.

The body has tight mechanisms in place to ensure water volume despite varying levels of fluid intake. First is through osmotic sensing mechanisms, including the release of arginine vasopressin (AVP) which messages the kidneys to conserve water through reduced urine output. Second is through the triggering of thirst.

Electrolytes, especially sodium and potassium, produce osmotic pressure needed for water to go in and out of cells, so the body is tightly regulating them, too. In fact, two-thirds of water is intracellular and one-third extracellular.

In short, the body works to maintain total body water within a narrow range by manipulating urine volume, electrolyte balance, and thirst.

“The maintenance of body water balance is so critical for survival that the volume of the body water pool is robustly defended within a narrow range, even with large variability in daily water intake.” Perrier et al, Eur J Nutr. 2021; 60(3): 1167–1180

Aging Pause Changes

Aging increases the risk of dehydration and blunts thirst. It also takes longer for older individuals to restore fluid balance after dehydration, compared to younger people.

This is attributed to slower kidney function, reduced muscle mass (which contains high amounts of water), and a lagging thirst sensitivity to extracellular volume. Total body water also decreases with age, mainly because of declines in muscle mass, as muscles are 70-75% water!

Although people over 65 frequently experience these changes, like everything related to aging, it doesn't happen in one day but is likely a gradual change that has an effect at midlife.

The change in hormones also affects women as they approach menopause. That's because estrogen and progesterone play a role in body fluid and sodium regulation. Estrogen, specifically, has been discovered to enhance osmotic sensitivity.

A series of studies with women 19-35 showed that when estrogen rises, it takes a smaller increase in osmolality to trigger AVP release. Remember that AVP tells the body it needs more water, thus increasing thirst and slowing urination.

Estrogen helps the body hold on to water, including intracellularly, which is beneficial to ensure hydration.

In an older study researchers attempted to isolate the effect of estrogen by giving a small group of postmenopausal women estrogen (and a control group without estrogen), infusing saline and allowing them to drink water. Although both groups drank the same amount of water/infusion, the estrogen group had a higher AVP, lower urine output, and reduced sodium excretion.

This is also why, when starting hormone therapy or oral contraceptives, some women experience bloating and weight gain because of water retention.

Below are symptoms that could indicate dehydration or suboptimal hydration (a few which I had).

Tired, dizzy, or lightheaded

Orthostatic hypotension

Dry mouth, lips, and tongue

Headaches

Dry skin

Decreased exercise performance

Few trips to the bathroom/Concentrated urine

Fatigue

Lack of focus

Muscle weakness

Rapid breathing

Muscle cramps

Palpitations

GI disturbances/constipation

What are the health implications?

The first thing I thought was: What’s the big deal? If the body goes to great lengths to defend water balance, won’t it be okay even if fluid intake isn’t robust? Well, now we have studies showing benefits to hydration, water intake, and urine volume.

First are the cognitive effects. Researchers followed 1957 adults (ages 55-75) with metabolic syndrome in the PREDIMED-Plus study for 2 years. Serum osmolarity (total solutes per liter) documented hydration status, and they assessed cognitive function and water intake.

The study revealed that a decline in cognitive function was associated with higher serum osmolarity, indicating poor hydration.

Another study using data from 11,255 adults over a 30-year period found that those with serum sodium in the higher normal range–another sign of poor hydration - were at greater risk for several chronic diseases and showed more signs of biological aging, than those at the lower normal range

“The results suggest that proper hydration may slow down aging and prolong a disease-free life,” said Natalia Dmitrieva, Ph.D., a study author and researcher in a press release.

Researchers believe this has to do with chronically elevated levels of AVP. Besides being an antidiuretic hormone, AVP also stimulates the liver to make glucose, which could negatively affect blood sugar regulation.

Epidemiological studies have established a link between higher AVP levels and an increased risk of kidney decline, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. That being said, we don’t have studies showing lower AVP through water helps reduce these diseases.

Then there’s the benefit of having adequate urine volume which helps flush out kidney stones and bacteria.

A 5-year randomized control study had half the subjects increase their water intake to achieve 2 liters of urine volume. Over the course of the study, the recurrence of kidney stones was 12% (2.5 liter urine) in the intervention group and 27% in the control (1.2 liter urine).

There was another randomized control study with 140 premenopausal women suffering from recurrent UTIs. Those who increased their fluid intake by 1.5 liters to achieve a total water intake of 2.8 liters and urine volume of 2.2 liters decreased the risk of UTIs by 48%.

Of course, this isn’t conclusive research, but it shows that hydration is important to health as we age. But I also wanted to revisit the potential health issues of too much water. You know, just in case.

Dangers of water intoxication

Believe it or not, until the late 1960s, coaches discouraged runners from drinking fluids for fear of gastrointestinal side effects. Yet a paper in 1969 entitled “Danger of an inadequate water intake during marathon running,” changed that.

Despite the fastest runners being the most dehydrated, the article emphasized their higher core temperature.

The popularity of marathon running led to the widespread practice of pushing water, resulting in cases of water intoxication being discovered.

Excessive water intake within a short period can lead to hyponatremia, where the kidneys cannot excrete the surplus water, causing low sodium levels. In a case-control study of 88 participants in the London Marathon, 12.5% had asymptomatic hyponatremia with a fluid intake of 3.6 liters.

“…the key factor leading to water intoxication was misinterpretation of the medical advice provided (such as: ‘drink plenty of water’; ‘as much as you can’) and the assumption that drinking more would lead to better outcomes (‘the more you drink, the better the test results).” - Ragan et al, MJ Open. 2021; 11(12): e046539.

According to a review on those who experienced water intoxication, the average water consumption was 8 liters of water or 5.3 L over a 4-hour period. Half had a psychiatric illness, and a good portion were exercisers.

Compare this to the 2-3 liters recommended and you can get an idea of what too much water looks like. The reality is most people have the opposite problem of getting too little water. In fact, international surveys estimate more than half of adults drink less than what’s recommended.

Which takes me to my next question.

How much water do we need?

Water or fluid intake recommendations vary from health organizations. The Institute of Medicine set an adequate intake for water in 2005 in women, almost 20 years ago, at 2.7 Liter/day total with 2.2 liters coming from fluids (9 cups).

We get roughly 20% of our fluids from food and 80% from beverages, including water.

To fill in the gap, in 2021 a group of researchers some involved in Donone’s research Hydration for Health proposed an evidence-based definition of proper hydration to include sufficient water intake to avoid excessive AVP secretion and ensure adequate urine volume:

We suggest that daily total water intake for healthy adults in a temperate climate, performing, at most, mild to moderate physical activity should be 2.5 to 3.5 L day−1. While total water intake includes water from both food and fluids, plain water is the only fluid the body needs. Plain water and other healthy beverages should make up the bulk of daily intake.

[There are 4.2 cups in a liter. If we say you are trying to get 3 Liters a day and 20% of fluids come from food that would 2.4 from beverages, that would be 10 cups of fluids/day.]

Those who are highly active or sweat a lot, likely need more. The NASM recommends 4-22 ounces fluid two hours before exercise, 6-12 oz water or sports drink every 15-20 minutes during exercise, and 16-24 oz of water or a sports drink after exercise.

Yet water needs are highly individual, and even if we get the studies we need, fluid needs will vary based on someone’s size, activity, health status, medication use, and other factors.

Researchers assess hydration by measuring urine specific gravity of less than 1.013 and/or serum osmolality of 500 mOsm/kg.

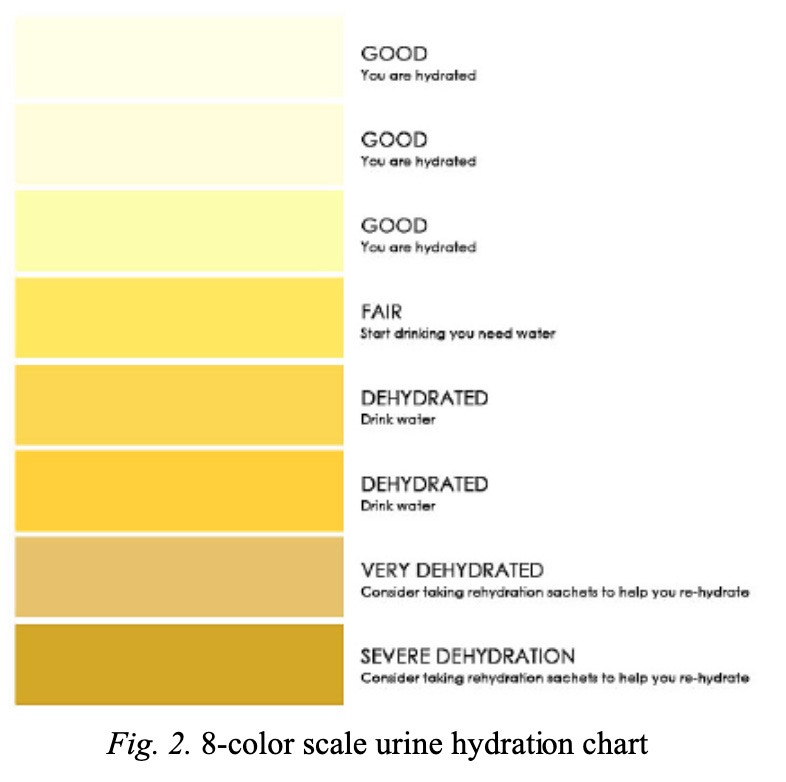

But the easiest assessment to do at home is a urine color of 3 or below (see chart) and voiding (pee!) 5-7 times per day, which suggests optimal hydration status. If your urine has no color, that could mean over-hydration.

Check out this hydration calculator that can help individual fluid intake, which considers your fluids, exercise, age, height and weight.

Yet as I increased my water intake and urine volume, I wondered if I was absorbing enough. If estrogen helps women hold on to water, did I need to add electrolytes?

The Beverage Hydration Index

Searching for an answer to this question led me to The Beverage Hydration Index (BHI). Like the glycemic index, BHI shows the rate at which different fluids affect hydration.

Both fluid volume and sodium affect the rehydration process. Electrolytes like sodium and potassium help increase the rate of water absorption.

In 2016, researchers tested a variety of beverages to help quantify how well they hydrate individuals. Seventy-two males consumed 1 liter of water or other beverages over 30 minutes, and the researchers measured their urine output over 4 hours.

The calculation of the BHI was done, as shown below. Most hydrating were oral rehydration (electrolyte) solutions and milk.

In a 2021 study with young adults, researchers calculated the BHI and discovered that electrolyte beverages had the greatest hydration effect.

I decided to try electrolyte mixes that are all the rage these days. I’m most active very early in the morning and my breakfast is low in sodium, the most important electrolyte for water absorption.

I’ve started using LMNT, which is high in sodium, but I’ve been trying half a serving at a time. They are also Cure and other brands, with lower sodium content.

What if the hydration problem is a bigger deal than we thought?

They conducted the first BHI study on young males and the second one with young adults. I wonder how this would go for midlife women before and after menopause.

I wish we had more data to see if perhaps getting a balance of electrolytes like sodium and potassium throughout the day helps with water absorption, especially after losing the boost from estrogen.

Something caught my eye in the hydration and cognitive study mentioned earlier. In the adults aged 50-75, 80% fulfilled the water recommendations, but serum osmolarity indicated that 56% were dehydrated.

What if hydration is a bigger issue than we think? As the body attempts to hold on to water, perhaps it pulls back from producing synovial fluid in joints (hello joint pain) and saliva in the mouth (hello dry mouth).

Low saliva levels have also been linked to an increase in GERD, which jumps at midlife. Not to mention the risk of UTIs and metabolic health. Of course, no one can say hydration status causes these things, but what if plays a significant role?

Could it also contribute to brain fog, palpitations, and other menopause symptoms? A recent paper implicates hydration in muscle function and quality, too.

Not to mention poor hydration status also has been linked to nervous system changes, low mood and anxiety.

It's a lot to consider. Let’s recap what we’ve learned so far.

Summary

Water plays an important role in health, including metabolism and transport of nutrients, flushing out waste/bacteria, lubrication of joints/skin/mouth and many other functions.

With Aging Pause, hydration status is at risk in women because of delayed or inhibited thirst, slower kidney function, decreased muscle mass, and lower amount of retained water (i.e., lower estrogen).

Our body fiercely defends total water volume, producing arginine vasopressin (AVP) hormone to slow down urine output and trigger thirst.

When fluid intake is chronically low, the subsequent increase in AVP has health implications, including altered glucose metabolism. Studies have also shown that higher urine volume reduces the risk of kidney stones and UTIs.

Although we need more studies, poor hydration status (measured through osmolality/high normal sodium) has been linked to lower cognitive function, kidney disease, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes.

More water is not always better, and research shows that people with water intoxication consume on average 8 liters per day or 5 liters over four hours. Endurance athletes and those with psychiatric illnesses are at greatest risk.

Water guidelines from different organizations vary but most are based on adequate intake, which are averages of what most people consume.

In 2021, a group of scientists put together guidelines indicating most adults with light to moderate activity need 2.5-3.5 liters a day through fluids (80%) and food (20%). A blood osmolality <500 but more realistically is to have urine color <3 on the color chart and 5–7-bathroom visits.

[There are 4.2 cups in a liter. If we say you are trying to get 3 Liters a day and 20% of fluids come from food that would 2.4 from beverages, that would be 10 cups of fluids/day.]

There are no guidelines tailored to life stage, physical activity, size, health/medication use, and other key factors. For individualized needs, checkout this hydration calculator. And if you have any health conditions, check with your healthcare provider.

The hydrating effect of different beverages vary and people who lose water and sodium through sweat may benefit from adding electrolytes to drinking to replace losses.

It’s possible hydration may be a bigger issue than we think, affecting everything from joint pain to dry mouth to muscle function and quality. But we need more research to figure it all out, including the best way to hydrate.

Hydration: another piece to the midlife health puzzle

Here we are, once again, left with little data and unanswered questions. Since adding the electrolytes mix before, during, and after my workouts, I feel better hydrated and haven’t had those dizzy standing episodes.

But that’s just an antidote, not evidence. Let’s add hydration to the long list of things we need to study in midlife women.

In the meantime, do what you can to stay hydrated with what we know today.

Have you noticed changes to your hydration status in midlife? Let’s talk about it in the comments.

The information in this post is meant for educational purposes and not to replace medical advice. I encourage women to bring this information to their medical providers while they figure out what is right or them.

Excellent article! I've found that electrolytes are essential for me now especially when I train but because I live in a hot country, I need them on most days. Seems it's not just anectodal.